Disciplinary Differences in Academic Writing Reflected by Reporting Verbs and Reader Pronouns

Table of Contents

In academic writing, should we write “I think”? Should we refer to the readers? Professors’ answers to these questions diverge considerably, thus confusing students taking courses in different disciplines. For example, my Philosophy professor advocates using “I think” and reader pronouns, while my Econometric professor recommends not using them. This phenomenon can be explained by the disciplinary differences in the perceptions of the authors’ rhetorical-situated identities in texts (Hyland, 1999). Therefore, this essay aims to identify such disciplinary differences by analyzing the use of reporting verbs and of reader reference that reflect rhetors’ idea ethos in Econometrics and in Philosophy.

Methodology

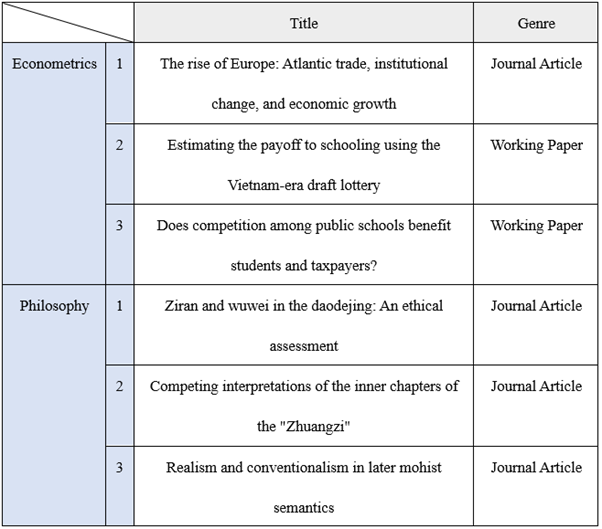

Three sample articles were chosen from each discipline, and they are compatible because of being either working paper or journal articles (Table 1). To be more precise, the focus was narrowed to the discussion section where arguments are developed, instead of the entire article. The two linguistic features analyzed are the frequency of reader pronoun, such as “you” or “we,” and the type of reporting verbs used. Reporting verbs are classified by Caplan (2012) into two types: evaluative verbs like believe, related to opinions and implying authors’ positions, and neutral verbs, indicating the obtaining of facts, such as write, know, or discover.

I used AntConc to calculate the ratio of evaluative reporting verbs to neutral reporting verbs and to count the frequency of reader pronouns like “you” and “we.” Note that not all “we” refer to the readers for that it could also refer to a group of authors, in which case it is a personal pronoun, referring to the authors, not reader pronoun.

Table 1. Sampled Articles in Philosophy and Econometrics.

Data Analysis

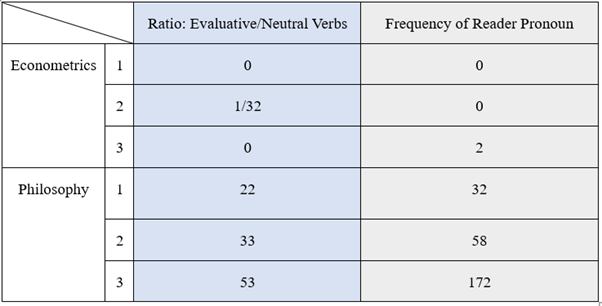

Table 2. The Ratio of evaluative verbs to neutral verbs and the frequency of reader pronoun.

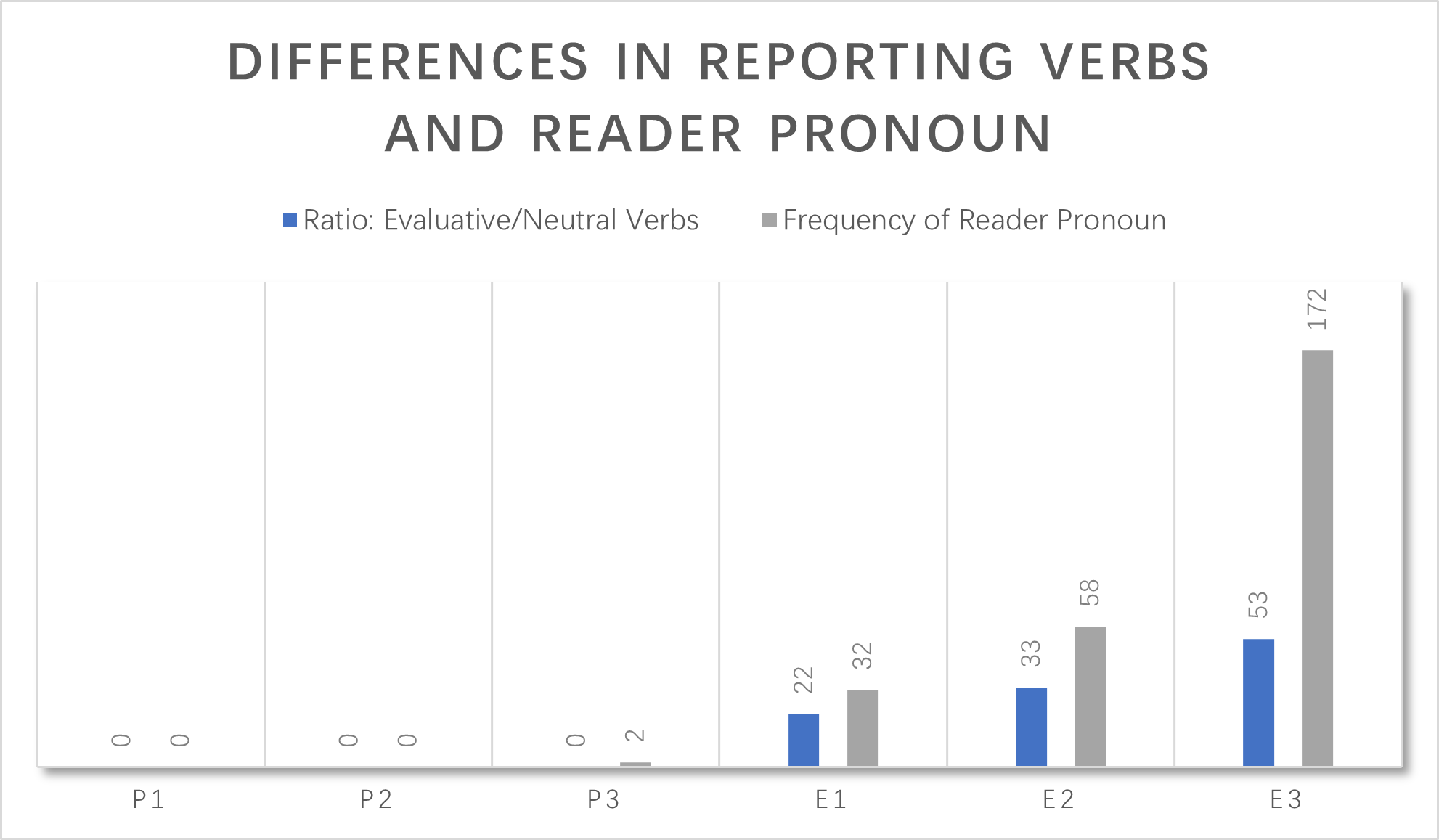

Figure 1. The Ratio of evaluative verbs to neutral verbs and the frequency of reader pronoun (values rounded to the nearest integer).

Table 2 and Figure 1 show that the ratios of evaluative verbs to neutral verbs are significantly larger in Philosophy articles than in Econometric articles. Also, the results also report that reader pronouns are almost absent in Econometric articles, but they appear frequently in Philosophy paper. Examples of reporting verbs used are listed below. Econometrics articles prefer neutral reporting verbs to evaluative reporting verbs:

-

“We document that…” (Acemoglu, Johnson, & Robinson, 2005, p. 546).

-

“We suggested that Atlantic trade contributed to…” (Acemoglu, Johnson, & Robinson, 2005, p. 572).

-

“Panel A reports estimates…” (Angrist, & Krueger, 1992, p. 14).

-

“The column three estimated show that…” (Hoxby, 1994, p.19).

Conversely, Philosophy articles give priority to evaluative reporting verbs:

- “I suspect that Zhuangzi though that…I think, the choice that Mencius and Zhuangzi…” (Van Norden, 1996, p. 9).

- “The way I read it…” (Stephens, 2017, p. 533).

- “I believe that this formal way of…” (Stephens, 2017, p. 534).

The followings are examples of reader pronouns. Though the sampled Econometric paper almost uses no reader pronoun, the chosen philosophical articles utilize a considerable amount of them:

- “We need to explain how we might interpret ‘nature’…” (Lai, 2007, p. 329).

- “Say you are on the other side of the room from me…” (Van Norden, 1996, p. 3).

- “We are first stuck by the mysterious image…” (Van Norden, 1996, p. 4).

- “On this point, we can first note that…” (Stephens, 2017, p. 539).

Discussion

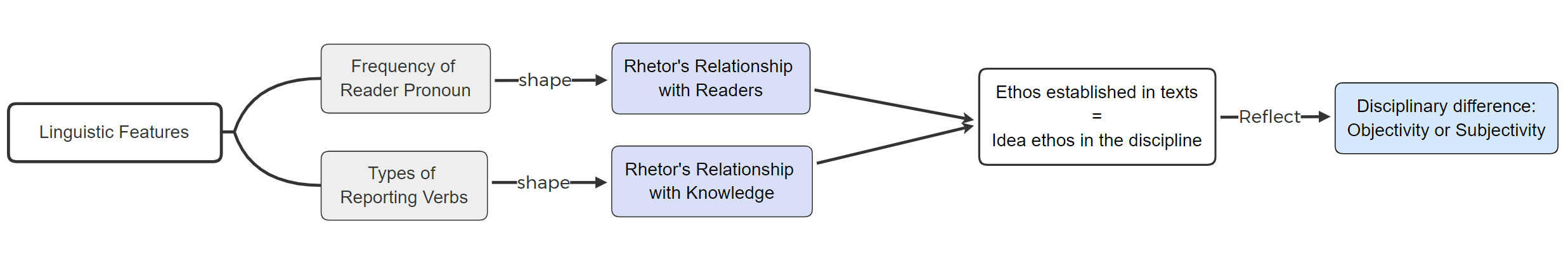

With a model developed (Figure 2), this section explores how the linguistic features shape ethos and so reflect the underlying disciplinary differences. Ethos, defined as the author’s rhetorical identity, is always established by the texts (Grant-Davie, 1997). So naturally, linguistic features of texts impact ethos to be built (Covino & Jolliffe, 1995). In this research, reader pronoun and reporting verbs shape the ethos built through texts, which corresponds to the idea ethos in given disciplines. Specifically, the frequency of reader reference indicates the rhetor’s relationship with the audience, and the choices of reporting verbs imply the rhetor’s relationship with the knowledge, which refers to the perceptions of the author’s contribution to the knowledge (Hyland, 2011). We would dig into the underlying disciplinary characteristics of Philosophy and Econometrics by examining why they have different idea ethos. The application of this model is detailed as follows.

Figure 2. Model of how linguistic features establish ethos that reflects disciplinary characteristics.

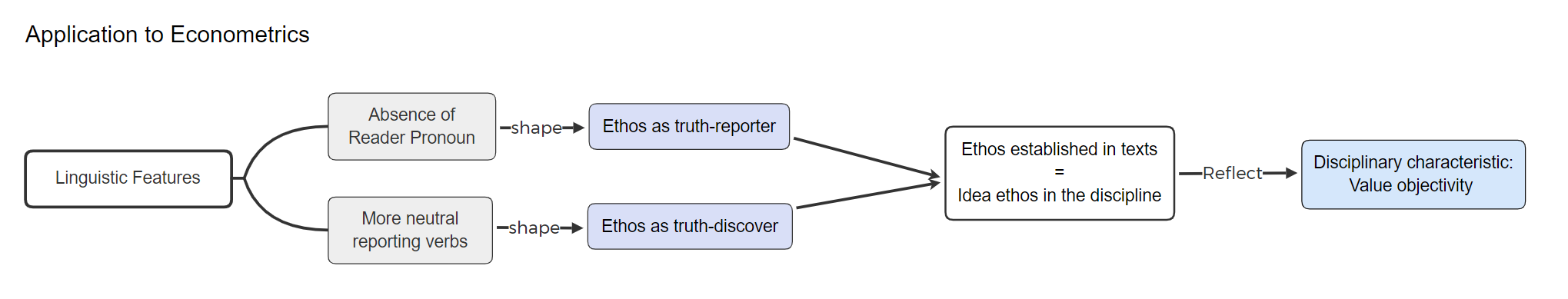

Econometric

Figure 3. Application of the model to Econometric articles.

In the sampled Econometric articles, the number of neutral reporting verbs overwhelms evaluative reporting verbs, which emphasizes the non-human nature of the research and so builds ethos as a truth-discover. Such stress on objectivity reflects the embedded epistemology that the truth stands independent of human perceptions (Hyland, 1999). Also, the absence of reader pronouns shows that the idea ethos of authority in Econometrics seems to be a truth-reporter, whose job is to give a speech to state the truth, not to hold a discussion and interact with the audience (Hyland, 2011).

Why can ethos as a truth discover and reporter be effective in Econometrics? This discipline seems to have an embedded the-more-objective-the-better belief. Rather than personal opinions, Econometricians tend to build research on data and models which are considered inherently blessed with reliability and credibility, just like Mathematicians and Physicists. The audience also expects professional data analysis and model development, satisfied with the objectivity presented in research articles. Such a tendency is so strong that Angrist, Pischke, and Ford’s (2009) criticize today’s Econometric research for overly relying on statistic and mathematic models like linear regression, instrumental variables methods, differences-in-differences methods and overlooking the research methods in social science.

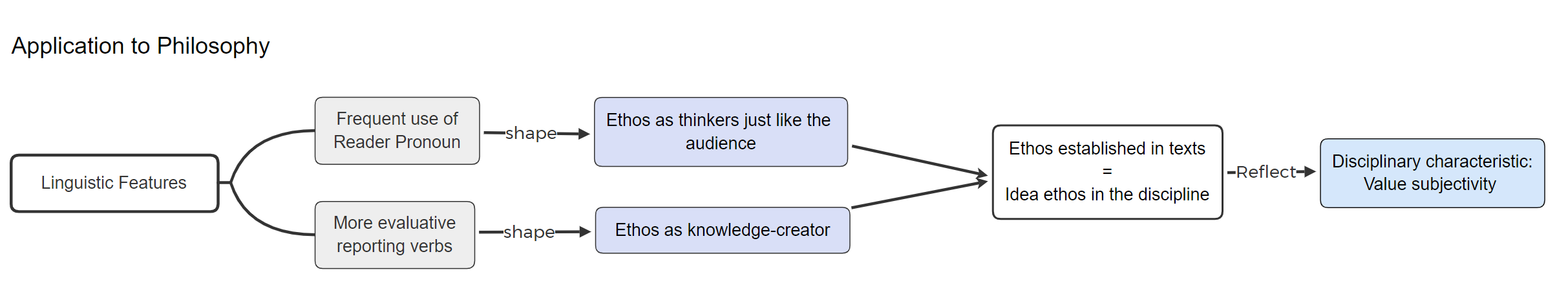

Philosophy

Figure 4. Application of the model to Philosophy articles.

Figure 4 shows how philosophy’s stress on subjectivity promotes the authors to use more evaluative reporting verbs and reader pronouns. Frequent evaluative reporting verbs build ethos as knowledge-creator, which means authors’ personal opinions contribute to the invention of new knowledge, not just describing it (Hyland, 1999). This kind of reporting verbs also shows rhetors’ respect to the audience and the acknowledgment that there is no absolute rightness in the world. Meanwhile, the heavy use of reader references develops the ethos as a thinker over philosophical issues just like their audience, putting themselves on the same side with the readers (Hyland, 2011). In this way, the writers engage the readers in a philosophical conversation, making them more willing to make efforts to follow the ideas in texts.

Why is ethos as a knowledge-creator and a thinker like the audience convincing and authorial in Philosophy? Hyland’s (1999) explains that philosophy values the originality of personal opinions, in which case subjectivity wins over objectivity. Accordingly, the audience expects to gain personal insights and engage in inspiring philosophical conversations.

Conclusion

To conclude, Philosophy values subjectivity, promoting authors to build ethos as knowledge-creator and to engage the audience into a conversation with the frequent use of evaluative reporting verbs and reader references. Conversely, Econometrics emphasizes objectivity, making the author more likely to choose more neutral reporting verbs and almost no reader reference to establish ethos as truth-discover and describer. More generally, the extent to which a particular discipline values objectivity would affect the ethos the rhetors try to build and the linguistic practices they apply. Therefore, when coming back to the questions presented in the introduction—whether and when should we use reader pronouns and “I think”—the answer might be that it depends on to what extent the effectiveness of arguments is built on objectivity.

These generalizations make great sense to students at DKU who receive liberal arts education and are encouraged to explore various disciplines. When writing essays and research reports in different courses, we could determine whether to use reader pronouns and what reporting verbs to choose based on the idea ethos in given disciplines. For instance, reader pronouns might win your essays better grades in Philosophy 102 and Social Science 101, and neutral reporting verbs, compared with evaluative reporting verbs, are more suitable for lab reports in Biology 201 or Physics 101. Additionally, the choices of reader pronouns and reporting verbs not only depends on disciplinary features but also on your specific writing purposes. Take this essay as an example: though I involved no reader pronoun in the previous sections to demonstrate my confidence in this research, I utilized lots of them in this section to make the readers feel sitting in front of me and thus be more willing to accept my suggestions.

(1387 words)

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. (2005). The rise of Europe: Atlantic trade, institutional change, and economic growth. The American Economic Review, 95(3), 546-579. doi:10.1257/0002828054201305

Angrist, J. D., & Krueger, A. B. (1992). Estimating the payoff to schooling using the Vietnam-era draft lottery (NBER Working Paper No. 4067). Retrieved from National

Bureau of Economic Research website: https://www.nber.org/papers/w4067 Angrist, J. D., Pischke, J., & Ford. (2009). Mostly harmless Econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Caplan, N. A. (2012). Grammar choices for graduate and professional writers. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Covino, W., & Jolliffe, D. A. (1995). Rhetoric: Concepts, definitions, boundaries. National Council of Teachers of English. doi:10.2307/358722

Grant-Davie, K. (1997). Rhetorical situations and their constituents. Rhetoric Review, 15(2), 264-279. doi:10.1080/07350199709359219

Hoxby, C. M. (1994). Does competition among public schools benefit students and taxpayers? (NBER Working Paper No. 4979). Retrieved from National Bureau of Economic Research website: https://www.nber.org/papers/w4979

Hyland, K. (1999). Academic attribution: Citation and the construction of disciplinary knowledge. Applied Linguistics, 20(3), 341-367. doi:10.1093/applin/20.3.341

Hyland, K. (2011). Disciplines and discourses: Social interactions in the construction of knowledge. In D. Starke-Meyerring, A. Paré, N. Artemeva, M. Horne, and L.

Yousoubova (Eds.), Writing in the knowledge societ (pp. 193-214). West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press and The WAC Clearinghouse.

Lai, K. (2007). Ziran and wuwei in the daodejing: An ethical assessment. Dao, 6(4), 325-337. doi:10.1007/s11712-007-9019-8

Stephens, D. J. (2017). Realism and conventionalism in later mohist semantics. Dao, 16(4), 521-542. doi:10.1007/s11712-017-9575-5

Van Norden, B. W. (1996). Competing interpretations of the inner chapters of the “zhuangzi”. Philosophy East & West, 46(2), 247-268. doi:10.2307/1399405